How Chords are Made

So, with the information we have from the last lesson, we are able to work out how chords are made and how they have certain sounds. Now chords are made using the very principle we spoke about in the last lesson, except they take multiple notes.

I apologise in advance, this is quite a theory based lesson but ill make it as fun as I can to get through!

Firstly, lets talk about chords and what types we can have. We know about Major Chords and Minor Chords, but there are many more. Before we get on to the others, let’s discuss how major and minor chords are made.

Let’s take A Major. If we look at the shape that we learned in one of the earlier lessons, we can see it looks a certain way. If we compare this to the fret board chart that we have seen a few times, we can put some notes on the fingers and the notes that we are playing. I have attached a picture with the notes on the diagram to show you which notes are being played.

As you can see, we are playing only 3 notes, multiple times: the notes: A-C#-E. This is why chords are known as "triadic" as they only contain 3 notes, they are just repeated up or down an octave.

We can see the intervals that make up this chord. So A-C#-E in intervals would be 1–3–5 (Because the notes from the key "A" are A B C# D E# F# G, we just count up the intervals ). Now what you see with that combination of numbers is the formula to creating a major chord. In earlier lessons, we spoke about moving one of the major chords notes down to create a minor chord.

The note we move down is the 3rd. This note will change the tonality of a chord and is important to creating qualities of chords.

So If we take this information and drop the 3rd a semitone we will get A–C–E. If we were to turn this in to a formula it would be 1–m3–5, as we are flattening the 3rd interval. This gives us the pattern for a Minor chord. We will look in to why in the future, but for now, just understand that the 3rd is one of the most important notes in a chord as it defines what kind of chord it is.

This is the first step to understanding how chords are made. There are a few things we have glossed over such as keys and how they are made, other chords and interval patterns, and a few other areas, but for now we will keep it there and fill in the gaps later.

We'll leave it there for now and get back in to playing. Just look out for the differences between major and minor chords, try and identify the 3rd note that is different between them. Actively thinking about this will make future learning a lot easier!

So we understand how chords are made by taking notes from a scale and putting them together. It's technical name is “Harmonising a scale” but don't worry too much about remembering it, knowing how it works is more important.

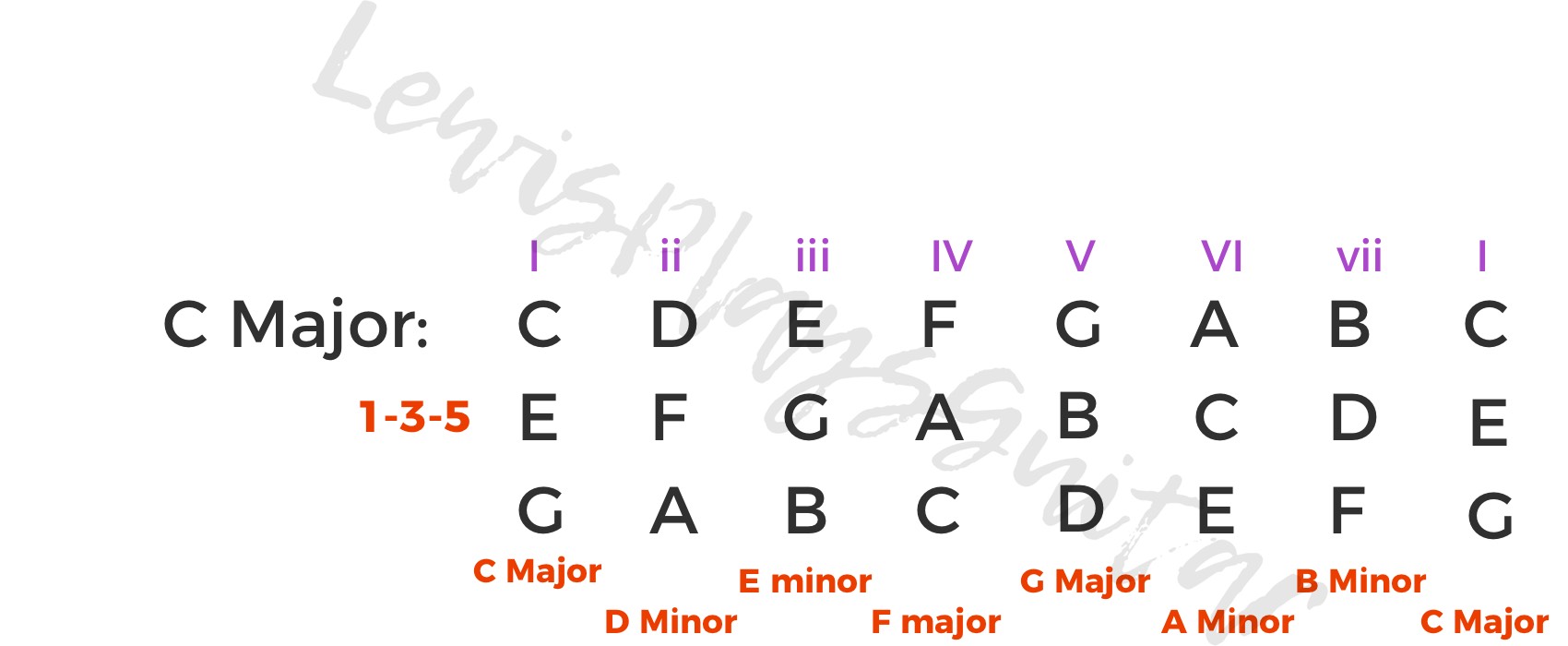

If we write down all the notes in a scale (we'll use the C Major scale, and write them on top of each other 2 notes apart, it should look similar to something below. If we read the notes going down, they should create the 1-3-5 triad we had earlier, and this is a really easy way to find all the chords that will work together in that key, perfect when you want to write your own songs!

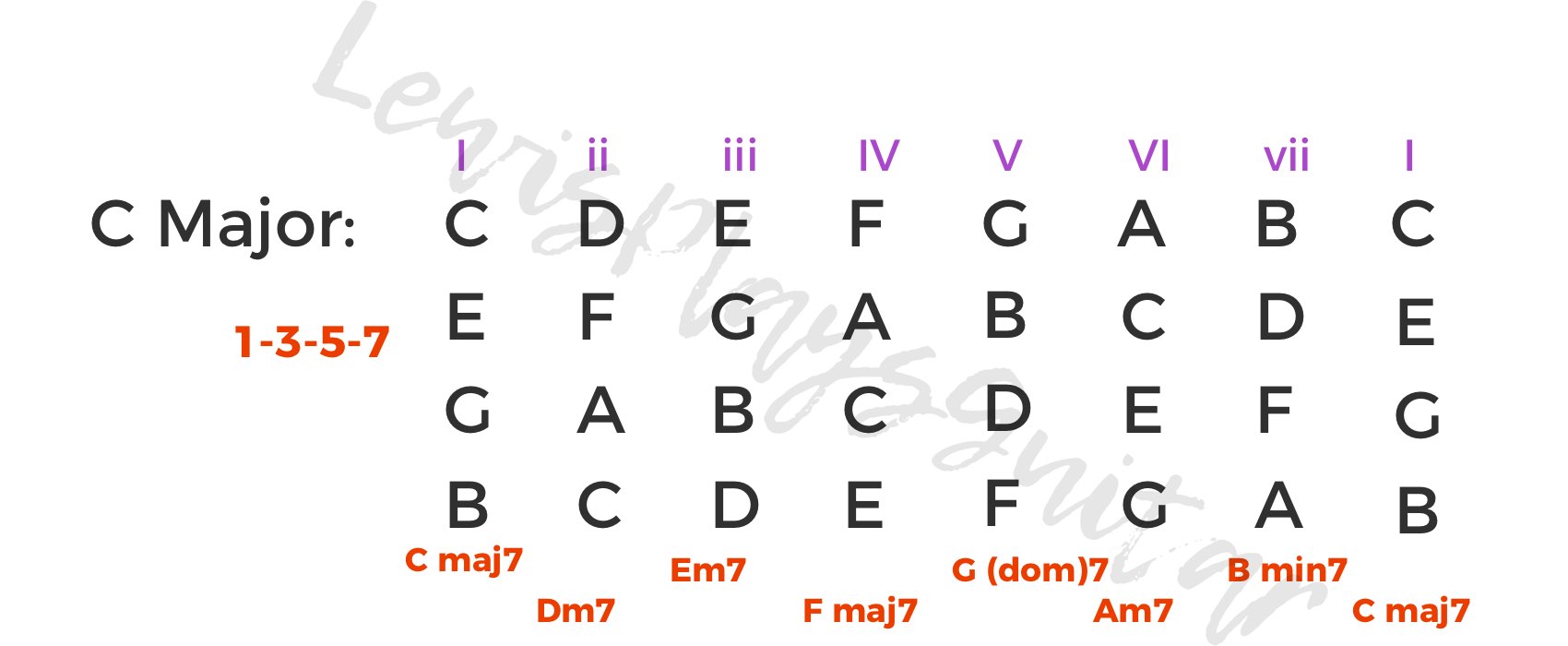

The technical term for this is "Stacking Thirds", which just means You start on the Root note (C), add a 3rd on top of that (E), then add another 3rd on top of that (G) and there is your triad. You can continue this pattern to create 7th, 9th, and other weird and wonderful chords, but more about that in the future lessons!

So we have started on another note and taken the 3rd interval from the scale starting from that note, that gives us the chords below. This can also be don’t with 7th chords and will create all of the 7th chords that will work. These are the chords within the key of C major. These chords will all work with the scale of C and can be used to write songs and progressions. Each of the chords are numbered with Roman Numerals. This makes it easier to distinguish when were using a chord instead of something else that used a number. The chords are in purple above the chart. Notice the lower case and upper case spellings. These indicate Major or Minor depending on the capitalisation.

Similar to the natural minor scale, the chords repeat from the 6thdegree of it’s relative major scale in the same pattern. This can be useful when figuring out chord in a natural minor progression.

I would suggest learning the pattern of the chords (sevenths):

- Major (maj7)

- Minor (min7)

- Minor (min7)

- Major (maj7)

- Major (dominant 7)

- Minor (min7)

- Diminished (min7b5).

There are many chords and their names will often clarify what is changed to the chord. Chords with extensions will be easy to break down, you will just need to identify which part needs to be broken down. For instance, Dm7b5 looks complex, but if you break it down, the first part Dm means we have a 1–b3–5 interval, then add the ‘7’ interval (we are to assume that the 7 is minor, as the chord is a minor chord. If it was major it would have ‘maj7’ and would look like this: Dm(maj7)b5) so we get 1–b3–5–b7. We would then add the final part which is the flat 5, so we put that into the formula making 1–b3–b5–b7 and we then put the notes in from the D scale.

And there we go! The notes in this chord will be D, F, Ab, C!